printed in Flying Magazine, May 1949

When I think of Saipan, I think of the Marines and

the C-46 I jockeyed around the Pacific during the war.

And every time I climb into a cockpit, I force myself to

re-live a hellish 30 seconds or so I spent on Saipan

while starting a routine flight mission. I re-live those

seconds because they taught me a flying fundamental I

don’t ever want to forget.

All pilots know that you can’t overlook the

checklist. It gets to be almost habit after a while. If

you’ve logged hundreds of hours in the same type of

plane, you give it that pre-flight check

automatically. You go back, you go forward, you go down,

you go across the instrument pattern.

photo of Tyrone in Saipan, 1945

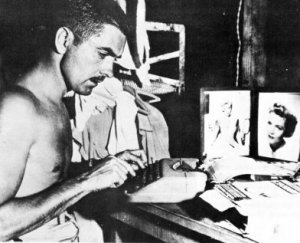

photo of Tyrone in Saipan, 1945(wife, Annabelle's photo on desk)

During the war I flew a Curtis Commando week

after week, month after month. I think I knew its

insides better than I knew what was in my pockets.

And, like a lot of other pilots, I got careless.

The hydraulic system on the C-46 is somewhat

complicated. Under the condition we flew the planes, the

seals for flaps and gear had a tendency to dry up

easily. We had to actuate them frequently to keep the

actuating cylinders flexible and to make certain we’d

lost no fluid from dried seals.

So, habitually, I’d actuate the flaps while waiting

on the line-just to make certain everything was all

right. I’d flip them up and down, up and down.

Then, taxiing, I’d flip them up and down again.

In our squadron it was SOP (standard operating procedure)to go through three full

cycles on the flaps. First, on the line or in the

revetment, again while taxiing for take-off, and once

again after final mag check.

That morning on Saipan I was hauled out of bed at 5

o’clock for a rush flight to Okinawa with a heavy load

of materiel and four or five men. I picked up my

co-pilot---a new one, checked the plane, and we were

ready to go.

I wanted to be extra certain those flaps were okay,

just in case I should need them on take-off. I made the

prescribed check in the revetment and another one while

taxiing for take-off. Then, while we sat there on the

end of the runway waiting for a bevy of planes to take

off, I checked it again. We went through the entire

check-off list.

My co-pilot got clearance, nodded to me, and off we

went. The C-46 scuttled down the runway while I kept

watching for the prescribed number of inches on the

manifold pressure. I knew immediately something was

wrong. The plane wanted to come off in about 1,000 feet!

And we were loaded to the gunwales.

Down the runway the plane barreled, trying to pull

off, with me pushing hard on the yoke to keep in on the

ground. Second by second we were eating up that runway,

roaring toward the end-and I had a quick vision of what

would happen: We were lurching along at 60 m.p.h. Then 65. And faster.

The last few feet of the runway would

be coming up soon, and I’d either have to chop those

throttles right away or there wouldn’t be time left to

do anything expect pray.

I couldn’t figure it out, though I was trying to

remember in those quick seconds everything that could

possibly be wrong. All I knew was that the darned plane

shouldn’t take off at that point, and yet it was tugging

and pulling to get off the ground. We were still

accelerating, and the remaining feet of the runway

looked like only inches.

Then off she roared. I couldn’t hold her down any

longer. As the plane lumbered off the runway, it seemed

to stagger. Desperately, I whipped a look around the

cockpit. Maybe the trim was off. I thought of a thousand

things, discarded them. I caught a glance at my

co-pilot, who about that time looked like a lad walking

the Last Mile.

And then we both looked down and at the same instant

saw what had happened.

I had left full flaps on the plane!

That spanking new co-pilot worked like a high -speed

machine. His arm shot down, and he dumped the flaps in a

fraction of a second.

There’s no need to tell pilots what happens when

you dump the flaps-especially with a heavily-loaded

plane the size of the Commando.

Ordinarily, the flaps would have been set at 15

degrees because any setting beyond that acts as a drag

and cuts down forward acceleration. Taking off with full

flaps, we became airborne faster (the tail just wouldn’t

stay down) but forward acceleration was slowed almost to

the stalling point.

So there we were. The co-pilot had dumped the flaps.

He knew what would happen then, and so did I felt like I

was piloting a big hunk of lead. We lost altitude-I

don’t know how much. I was too busy gunning the plane at

full throttle and rolling forward with all my might on

the trim tab to keep from stalling. The co-pilot

realized better that I that we were about one foot from

eternity.

My gear was up by this time, and we were still so low

that the prop tips were missing the ground by inches.

The red lights at the end of the runway were getting big

as cannon balls-and right behind them was a hill. Even

at that moment, while I was breaking out in a cold

nervous sweat, thought mirthlessly about the headlines

back home: “Tyrone Power’s Last Scene-A Smash Hit.”

But almost miraculously, we squeezed over that hill

with the old Commando’s engines screaming. The

rest of the ride to Okinawa was anti-climax. But today,

whether I’m flying a plane in California or in Rome, I

sit for a second or two before take-off and remember

that day on Saipan. It helps me remember that I’ve got a

lot to learn-and that in flying, you can’t afford to do

any forgetting.

non-profit site

© 2004-2011 tyrone-power.com

all rights reserved