Modern Screen

Modern ScreenFebruary 1959

Farewell

to a

Great Star

In the cold Spanish morning, he died.

Gasping for breath, his face red-splotched; still dressed in the bright robes of a Biblical king, he fought his final battle, and lost, surprised.

He was not used to losing. From the time a frail child, doomed by doctors -- "He doesn't assimilate his food, he's starving to death -- " proved the spirit could outwit the flesh, Tyrone Power had struggled for life.

Deeply rooted in the wonders of this earth, he'd lived a love affair. The sun had nourished him, and the skies, the seas, the hills. Pretty women had pleased him. He'd enjoyed his work, and many books, and children and music and food and drink.

At forty-four he was not ready to go. At eighty-five, he wouldn't have been ready either. There were too many places he'd never seen, too many tastes he'd never experienced.

He was a middle-aged man with the hungers of a boy. The year he was forty, he retackled the stage, because his Hollywood career left him unsatisfied. "Out of forty movies, I'm proud of four", he once said. "You can kid everyone but the person you shave." Only this year, he'd found the woman who would give him, he felt sure, the son he longed for.

the things he did . . .

Once Linda Christian, his second wife, had asked him where he wanted to be buried. He'd turned on her, eyes blazing, "Never speak to me of death!"

He was a man who had clung to the warm voices of friends, and left it to others to speculate on the cool tones of angels, yet he was dead, in Madrid, with so much left undone.

Ted Richmond, Ty's producer, cried as he tried to tell the cast of Solomon and Sheba the news. George Sanders, his co-star, cried as he choked out, "He was such a sweet person --" Gina Lollobrigida, his leading lady, cried as she sent for her husband to come and comfort her.

These are the ones he loved . . .

But Deborah Ann Smith Minardos Power, carrying a child who would never know his father, did not cry. And for her there was no comfort.

She sat in a chair in her hotel, arms crossed against her chest; she rocked back and forth, eyes blind with shock.

Later, the first numbness passed, shaken with terrible dry sobs, she moaned into the emptiness. "It isn't true," she said. "I don't believe it --"

From all over the globe came echoes of her cry. Tyrone's first wife, French actress Annabella, who had been his friend for twenty years, told her grief. "It's an unbelievable tragedy for all of us who knew and loved him -- but most of all a tragedy for Ty. He was looking forward to what he wanted most in the world -- a son."

These were his last

moments alive . . .

Henry King, who'd directed Ty's first screen test, uttered his wonder that such a brilliant career should come so abruptly to a close. "It seems incredible because Tyrone Power was a man surcharged with a love of life."

Linda Christian, mother of Ty's two daughters, trembled, opening a letter Ty had written the little girls. "Poor children," she whispered. "Poor children - "

So it was over. Within the week, a white-faced, pregnant girl would bring her husband's body back to his own country, to California. Once the boy had run and laughed and dreamed his dreams in the shining sands beside the Pacific; now the man was coming home to sleep.

A sickly infant, Tyrone Power, born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on May 5, 1914, puzzled the medical profession by clinging to life. His father, a famous Irish actor fast becoming a famous American actor, moved the family to Los Angeles when Junior was still an infant. "The climate will be better for him --" Tyrone, Sr. was right. The wilting baby bloomed. He lived in the open air, and grew brown and strong.

At eight, he appeared with his parents (his mother, Patia, was herself an actress) in the Mission play in San Gabriel, and after that, he knew what he wanted to do.

His parents separated. He and his sister, Ann, went back to Cincinnati with their mother. Tyrone, Sr. went off about his career. But the day Tyrone, Jr. got out of high school, he said, "No college for me, Mother. I want to be an actor."

She wasn't surprised. She wished him well, and sent him to join his father who was making a movie called The Miracle Man at Paramount. Tyrone the younger hung around, admiring, learning the ropes.

One night, the two Powers came home from the set, spent a quiet evening, went to bed. A few hours later, the boy was shocked out of sleep by a strangling sound. He rushed to his father's side. The older man died in his son's arms.

After that, Hollywood turned sour. Ty was lonely for his father, and he couldn't beg a job. A man named Arthur Caesar advised him to go to New York. "That's where you'll get experience --

He got experience all right. He found out you could make a cup of coffee last all afternoon at a cafeteria, on days when the weather was just too cruel to walk around in. He found out that cardboard's nearly as good as leather on the bottom of your shoes, except when it's raining.

Before the contract

And he found out that some big-shots have hearts. Katherine Cornell, remembering the father, took pity on the son, and gave him small parts in her productions of Romeo and Juliet and Joan of Arc.

He was incredibly handsome, a fact noted by movie magnate Darryl Zanuck, who signed him to a Fox contract. Twenty-one when he made Girl's Dormitory, Ty only had a bit, but the fan mail poured in. With Lloyds of London he became a full-fledged star. Maybe he was stiff, maybe he was stagy, maybe his diction was too careful, but he was gorgeous to behold, and the public adored him.

He drove himself. With each picture, he grew as an actor. "Work is my passion," he said, "my beloved mistress who takes all I have to give and who's welcome to it."

At twenty-five, Ty discovered work wasn't enough. He met Annabella Carpentier when they were making Suez, and they married, even though the fact that she was a divorcee meant they couldn't have a Catholic ceremony. Ty was Catholic, he'd hoped for the blessing of his church, but he needed Annabella.

"This woman's helped me discover in myself more than I've ever been able to find alone," he said. For a time, the Powers were blissful. Then, with World War II, Ty enlisted in the Marines. When he came back, his marriage was over. Nobody knew what had happened, except that the war had changed Ty. He was nervous, restless, confused, no longer able to lead the kind of life which suited his wife. He and Annabella had no children. Fretful and childless, why should they stay together? Regretfully, they parted.

In 1948 freedom was his idea. He didn't change his mind until he met Lana Turner, who handed him her whole generous heart. "He's the only man I ever loved," she said, and, in the background, Ty beamed, apparently content.

As a last gesture, a kind of final stretching of wings before he allowed those wings to be clipped again, Ty took off on a jaunt around the world. In Rome, he met Linda Christian, and that settled that. He surrendered his new-found freedom not to Lana, but to Linda.

In 1949, they were married. Linda'd told a friend she wanted a quiet wedding. "No expensive trousseau. No champagne. No crowds. A simple white dress and the mantilla my mother wore at her wedding."

The actual event was more like a scene from a Cecil De Mille movie. The simple white dress cost a thousand dollars, crowds rioted outside the church screaming, "Ty il Magnifico," and "Viva Linda," boys sang to the music of a specially installed electric organ, while photographers hid among great banks of flowers.

Ty wanted a son, but in 1951, Romina was born, and the proud father forgot he'd had a prejudice against girls. Without children, he'd felt incomplete; being a father made him alive in a whole new way. His second daughter, Taryn, was born in 1953; and in 1954, the Power marriage ended. This time, it was the lady who'd got restless. Ty paid her off as generously as he'd paid off Annabella -- each ex-Mrs. P. was reported to get $50,000 a year -- and declared he was through with wedlock. "Nothing could make me try it again --"

Against the advice of almost everybody, Ty appeared in a stage adaptation of John Brown's Body. "They'll ruin you," said know-it-alls. "They always crucify Hollywood people." He couldn't be shaken. "I'm tired of the trappings of success, and none of the enjoyment -- "

And he was right. Afterward, he could sit back and read tributes such as Walter Kerr's, in the New York Herald tribune. "Power reveals an exciting capacity for ferreting out the precise meaning of a fleeting image, and a crisp, graphic talent for communicating his vision to an audience," wrote the often razor-tongued Kerr. "So far from being a motion picture mask, he is an actor of considerable variety."

Ty traveled. He played theaters in Dublin and London. He had a romance with Swedish actress Mai Zetterling, and he bought a yacht named The Black Swan (after a picture he'd made 15 years before) and he wore white shirts embroidered with black swans, and when he said he was having fun, most people would have believed him.

But there was something missing. He had secret fantasies about a woman who wouldn't be an actress, but would only belong to him. Of a son who would bear his name and be the theater's fourth Tyrone Power.

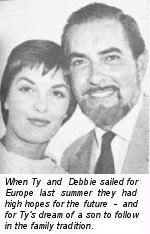

Then he met Debbie Minardos. She was twenty-six, a divorcee. She came from a small town in the South 'where everybody knows everybody and we don't even have numbers on the houses'. She was content to listen when he talked, to go home when he was tired, to laugh when he was happy.

With their dark hair, their dark eyes, Power and Debbie looked alike, and some people thought they were related. "Thank goodness we're not," sighed Debbie, and honest woman, honestly in love.

They were married on May 8th, 1958, in Tunica, Mississippi. "She's different," he said, wonder in his voice. "She has no ambitions, she doesn't care about expensive clothes or jewelry."

"He's beautiful," she said. "Every way there is, he's beautiful."

The location trip to Spain for Solomon and Sheba was to be in the nature of a prolonged honeymoon for Ty and Debbie, who planned side trips to Italy and Switzerland. From Spain, where she first discovered she was pregnant, Debbie wrote her family, I pray for a boy.

Read what you will into the line, the fervor was probably more for Ty than for herself. Debbie might have welcomed a child of either gender, but Ty's almost mystical need to sire an heir had moved her.

Debbie seldom stirred from her husband's side. As a joke, the producers of Solomon and Sheba put her in one scene, playing a concubine. "I don't give a hoot about acting," she said. "You're always underfoot anyway," they said. "May as well get paid for it."

A few weeks before Ty died, he'd had a heart checkup. Studio officials say now that there had been 'some concern about his health,' but that 'no one dreamed his life was in danger.'

Always, he'd been vulnerable to cold, and this winter, the cold in Madrid was bitter. He'd had an attack of dysentery, from which he seemed recovered, but even so, Debbie worried. On the morning of November 15ths, when he left for work, she made him promise to come back to the hotel for lunch. There was no premonition of disaster here, only an anxious wife who didn't like her husband's color, who wanted to make sure he wouldn't overdo.

The scene they were shooting that day was a duel between Ty and George Sanders. In bare feet, on an icy stone floor, the two men went to work, while all around them actors in flimsy costumes shivered, their breaths frosting the air.

Earlier, Ty had complained of a pain in his left arm and his abdomen, but he'd gone on working anyway. Suddenly he stopped, waved his hand in a 'cut' signal, sagged against a wall. His make-up man and friend, Ray Sebastian, loosed his breast plate and held a bottle of brandy to his lips. Ty was too sick to his stomach to swallow the drink.

Producer Richmond got him to Gina Lollobrigida's car, and to the hospital. Ty never recovered consciousness.

In Paris, Linda Christian said her astrologer had warned her that Ty would meet sudden death.

In London, Ava Gardner 'collapsed with grief.'

In Madrid, Deborah Power sat by herself, as the afternoon shadows deepened around her. Because she was young, and carrying a child, she would recover, she would go on. Because she had shared that passion for living which was Tyrone Power's greatest strength, she would learn to be happy again. But for a little while, all the lights in her world had gone out; and she was alone in that grey place, and afraid.

For all of us, a light has gone out. Tyrone Power was a gentleman and an artist. He was, to use his wife's words, beautiful, with a spirit both fierce and eager. He could be killed, but never beaten.

non-profit site

© 2004-2011 tyrone-power.com

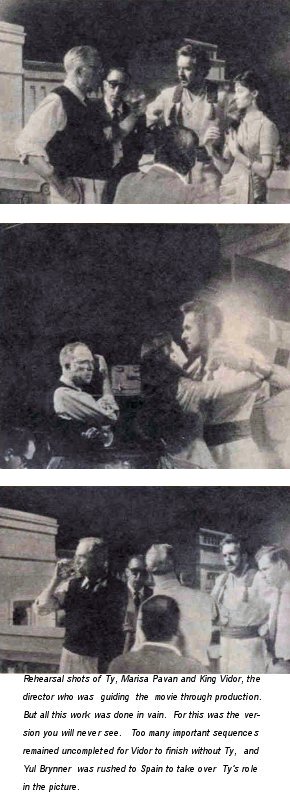

all rights reserved