reprint from Motion Picture magazine

July 1946

MOST OF US GO THROUGH LIFE as a punching bag for our emotions, slapped and pummeled this way and that by our worries, angers and desires. As we grow older, some of us acquire wisdom enough to stand firm against hard knocks. But some people never do get themselves into balance -- never find a philosophy which gives them stability and strength.

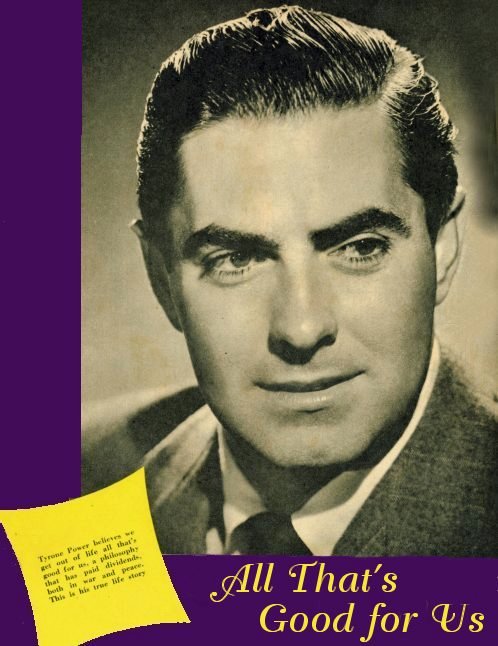

This is frequently true of actors, with their vivid imaginations and hair-trigger emotions. But Tyrone Power is one actor who seems to have crystallized a philosophy at the age of 7, and lived by it ever since. One evening he and his sister Ann, 5 years old, had just finished saying their usual prayers and clambered into their beds. They had been reciting the 23rd Psalm. Ann piped up, "What does it mean where it says, "The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want?"

Tyrone flopped over with a disgusted groan. "Oh, Ann, it means we may not get all we want, but we'll get all that's good for us," He snapped. "Now go to sleep."

The incident was characteristic of Ty, man and boy. He has what a Supreme Court justice once called "the instinct for the jugular" -- the knack of striking instantly to the center of a problem. He thinks fast and straight. At the same time, he's impatient with slower thinkers -- although in recent years he has learned to hide this impatience and even, sometimes, to drive it out of his thoughts.

But the philosophy which Ty saw at the heart of the 23rd Psalm has been his own philosophy all his life. Ever since boyhood he has been able to brush off worries and fears and keep driving ahead with the blithe certainty that "I'll get all that's good for me." Whenever he ran into a disappointment -- as he did time after time in the early days -- he's simply grin and mutter, "Guess it wasn't in the cards for me this time," and then start working and planning for the next time.

As a high school boy in Cincinnati, his highest ambition was to make the football team. He was thin and light, but he never worried about that. Each fall he turned out for football, was knocked down and trampled by the beefier boys for a week or two, then was dropped from the squad at the first cut. It didn't dishearten him. He'd try again next fall.

The years after he finished high school were full of disappointments and defeats that might have broken the spirit of many a youngster. He plowed briskly through them, always with the certainty that things would work out sooner or later. His mind already was made up, when he was graduated from high school at 17, that he would be an actor. At first his future looked bright, then slowly turned black.

His father was Tyrone Power, Sr., a brilliant stage star of the period. The elder Power took his son to Canada that summer for personal coaching in Shakespeare, then to Chicago for Shakespearean repertory. Young Ty played bits while his father starred. As soon as the season ended, Hollywood signed Tyrone, Sr., for the leading role in The Miracle Man and promised Junior a small part in the same picture. So father and son went to Hollywood together, in 1931, and the golden gates opened wide to them.

Young Tyrone was dreaming rosy dreams at this point about rolling straight ahead to stardom. The road seemed open before him. Then, like a clap of thunder, came tragic news. His father died suddenly on the set.

From then on the rains came down hard for a long time.

The small part he had been promised in The Miracle Man didn't materialize so he began looking for work. All doors were open to him because he was the son of the famous Tyrone Power; he had no trouble getting past reception clerks or butlers. Hollywood producers, agents and casting directors invited him into their offices, entertained him at their homes -- but they never gave him work.

If you haven't had professional acting experience and plenty of it, your chance of getting even a bit part in Hollywood is about one in ten thousand. Ty found that out. All his father's friends were delighted to talk to him by the hour, reminiscing about old-time stage experiences while he listened attentively; but whenever he ventured to ask for a movie chance, they'd gently stall him off. He hadn't enough experience, they secretly believed, so they didn't dare gamble on him.

Ty moved out of his apartment to a cheaper one, then moved again and again, always to cheaper rooming houses, as his money dwindled. This was the early '30's -- remember? -- when breadlines were everywhere and jobs were nowhere. His mother kept sending him money, but he sent it back with thanks. "I'll get along on my own," he'd write her. "Everything will work out all right."

This dragged on for two years. Frequently some influential movie man would send word for Ty to "drop in and see me," and Ty's heart would leap as he wondered if this might be The Big Chance at last. But each time the invitation would proved to be a purely social one. No one had work for him, and his savings kept dwindling.

One test of a champion is whether he can get up off the floor when he's knocked down. Ty was figuratively knocked down innumerable times, but he always bounced up again, and he never lost his grin. The repeated disappointments at the hands of his highly-placed Hollywood friends didn't shake his faith in himself or his destiny; he never gave a thought to looking for any other line of work.

The time came when Ty was skipping meals occasionally to save money and putting cardboard in the soles of his shoes because he couldn't afford resoling. But his letters to his mother remained as vigorous and cheerful as ever. His acquaintances never heard him complain. At last, however, he saw that he was butting his head against a stone wall. He might tramp in and out of Hollywood casting offices for the rest of his life, but he'd never get a role.

Characteristically, he didn't give up. He simply changed his point of attack. He decided to head for New York and try to crash the Broadway stage.

His mother was living in San Diego. He went there for a final visit with her, and then she happily saw him off -- never suspecting that he planned to sit in a day coach for the whole trip and live on sandwiches and cokes. (It wasn't until years later that he told her any of the hardships he went through at this period of his life.)

Ty's ticket took him only as far as Chicago. Instead of squandering more money on a fare to New York, he decided to stop awhile in Chicago and look for jobs there.

Once more he began pounding pavements. But this city proved to be different from Hollywood. There were young theatrical men here who had scarcely heard of Tyrone Power, Sr. They considered young Ty as a would-be actor in his own right instead of just a famous actor's son.

Chicago producers liked his looks -- his flashing dark eyes and sudden high-voltage smile. They liked his rich voice, and the lithe way he carried himself, and the quickness of his response to any suggestion they made. Here is a boy who will work hard and think fast, they said to themselves; he's thin as a racehorse but he's handsome, so maybe we should give him a try.

He began getting radio roles and dramatic parts in short-run stage plays with a stock company at the Century of Progress Exposition. He met a young fellow named Don Ameche who also was breaking into radio, and the two took a liking to one another. They've been fast friends ever since.

Tyrone stayed in Chicago for nearly a year. There were long periods when he had no work and sometimes the dark doubts of the future which attack all of us must have clustered pretty thickly around him. But he never gave in to them. His boyhood belief that we may not get all we want, but we'll get all that's good for us," kept him firmly on his feet.

Toward the end of 1934 the tide began to turn. He got an important role in a Chicago stage play which ran for eight weeks. With two months' pay in his pockets, the young actor felt richer than he had in years. He decided it was time to resume his journal to Broadway.

Broadway was tough, too. In six months, all he could get was a gob as understudy to Burgess Meredith in one of Katharine Cornell's hit plays -- and Meredith never missed a performance. So Tyrone held himself to a budget of $5.00 per week.

Months passed, Katharine Cornell's play approached the end of its run and nothing else was in sight for hi. But he stuck, and just before the play was to close -- thereby kicking him back among the crowds of unemployed actors -- he got the first big break of his career. Miss Cornell offered him a role in her production of Romeo and Juliet. After thinking over the proposition for about five seconds, Ty Accepted.

Romeo and Juliet was to open in the fall. This was late spring. So Ty filled in the gap by joining a summer stock company in New England. There he made a lot of heads turn, and Hollywood -- which had never been able to see him as an actor when he was under its nose -- began to take notice. A talent scout from one of the smaller movie studios offered him a contract.

Six months earlier he would have grabbed it. But now, with a contract from the great Katharine Cornell in his pocket, he could afford to pick and choose. A Broadway production seemed likely to teach him more than a minor role in a minor movie company. He declined the Hollywood offer with thanks. He told his mother with a grin, "Wait till 20th Century-Fox asks me -- then I'll go." Maybe he had a hunch that day -- because there certainly was no inkling that 20th actually would ask him before another year had passed.

That fall he made his Broadway debut as Benvolio, friend of Romeo. This was the pay-off for the years of coaching from his father and from his mother, who was a brilliant actress in her own right and a diction teacher as well. It was the pay-off for months of stud and practice in Hollywood, Chicago, and New York, when he had nothing else to do. It was the pay-off for his unconquerable determination to succeed in spite of a million rebuffs. He played his role like a polished professional.

Miss Cornell was so delighted she gave him a role in her next play, Saint Joan, after Romeo and Juliet finished its run. He made good in this one, too -- and then came the contract bid he'd awaited so long. It was, oddly, the very same company whose offer he'd jokingly announced he'd wait for: 20th Century-Fox.

So at last he went back to Hollywood , and soon thereafter the world was at his feet. He played a small role, then a larger one, in two light comedies; then Darryl Zanuck characteristically decided to gamble big stakes on this handsome unknown. He gave Tyrone Power the lead in the studio's million-dollar production of 1936, Lloyds of London.

As every fan remembers, he was a sensation. Overnight he found himself one of the world's great glamour boys. Money, applause, mobs of autograph-hunters, bushels of fan mail, any luxury he desired -- everything that goes with overwhelming success in Hollywood came to him with a rush.

His old acquaintances watched curiously to see how he'd take it. Would he begin to swagger and preen himself? Would he snub the humble people who'd helped him, here and there, in the days when he had nothing?

They soon discovered he wouldn't. Tyrone Power has never snubbed anybody in his life. On his first trip to New York after achieving stardom, he spent most of his time looking up old friends: people like the little restaurant owner who had fed him spaghetti "on credit" when he was a Broadway understudy; and the generous landlady who let him keep his room when he had no money for rent. From that day to this, wherever he has gone, he has made a point of hunting up any old friends in the vicinity.

There are likely to be many irritations in a star's life, but Ty kept himself in check and gradually built a reputation as one of the studio's most co-operative actors. He quietly accepted roles that didn't show him at his best, and played them to the hilt: a tight-lipped, mature-looking canal-builder in Suez, a ruthless political boss in In Old Chicago, a grim young count in Marie Antoinette, a thoroughgoing heel in

Rose of Washington Square. He soaked up all kinds of physical punishment without allowing a double to replace him: he jumped in the path of an 18,000-gallon flood in The Rains Came, stood up to a seventy-five-mile sandstorm in Suez, fell off horses in Jesse James, took three days of bare-knuckled pummeling from Don Ameche in In Old Chicago.

Tyrone always has been genuinely charming to women of all ages. (His mother has a photograph of him at the age of 4, ogling a little flapper of the same age.) They like him because he devotes his complete attention to whoever is his companion. He never takes his eyes off her when they're talking together. When he smiles at her, it isn't a mechanical showing of teeth, but a warm and friendly expression of feeling. He always likes the conversation to be about her not about him. His quick brain is always seeking little things to do for her, little things to say to entertain her.

This has been Tyrone's way, whether he was on a date or merely meeting someone momentarily. A former magazine writer, now in advertising, tells of a party for the press where Tyrone had agreed to be photographed individually with each writer present. When Ty and the cameraman came to her, she begged off: "I've been sick and I look all run down," she pleaded. "The picture wouldn't be any good - let's not waste the film."

Most glamour boys would have shrugged and strode on. But not Ty. He sat down, put his arm around her and said slowly and emphatically, "You do not look run down. You always look wonderful. I want to be photographed with you."

How could any woman resist that kind of charm? Annabella certainly couldn't. Ty first began to notice the little French actress when he pulled her out of the sandstorm in Suez. Soon afterward he began a high-pressure courtship, and, in 1939, they were married in Hollywood.

Annabella certainly couldn't. Ty first began to notice the little French actress when he pulled her out of the sandstorm in Suez. Soon afterward he began a high-pressure courtship, and, in 1939, they were married in Hollywood.

But his courtship didn't stop there. "Some guys figure that, once they've married the girl, they can relax," he has told his friends. "I claim you have to work at marriage to make it a success. You have to keep on being just as attentive, as considerate, as affectionate as you were the day you proposed to her."

Annabella seems to have met her husband halfway, for their marriage always has been an obvious success. She believes, as do most French women, that happiness lies in making her man happy. Ty gives her the credit for the smooth course of their love. "I'm high-tension, too impatient," he criticizes himself (although it's doubtful whether anyone else would verify this statement)."Sometimes I wonder how Annabella puts up with me, but she's always so patient, she keeps us on an even keel.

Their life together drifted along happily for two and a half years. Then one Sunday morning Ty switched on the radio and the news roared in that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. His eyes met hers. "Well, we're in for it," he said. Her shoulders lifted in a small Gallic movement. That was all. But each knew what the other meant. "It was the first good-bye," she said afterward.

Tyrone was classified 3A because of his dependents, but he began looking around to size up the various branches of the armed forces. He'd already decided to go in. He didn't, however, want to wear a uniform and sit in a swivel chair. This was high school football tryouts, in a way; he wanted to be in the thick of the fight, not in the grandstand.

He had learned to fly in 1938 and a combat pilot's berth looked good to him. But he was over age to be a flier, and the fact that he hadn't gone to college put him below the educational requirements. So he kept looking around. Then one day he heard a Marine officer give a talk explaining that "the Marines are first and foremost a combat outfit. Any Marine cook or doctor or correspondent knows that he may have to pick up a gun at any minute and start using it. There are no rear-echelon jobs in the Marine Corps."

That was for Ty. In August 2941 he enlisted in the Marines as a private.

"You're a coward," a studio wit told him. "Anyone who quits 20th Century-Fox for the Marines is a coward." Ty grinned at all the wisecracks, shook hands warmly with all the well-wishers and went off to war.

A Marine boot camp is no place for weaklings. It keeps a man on the run from dawn till dark: bayonet fighting, marching, shooting learning to kill a man with your bare hands, learning to knife him, learning to club him. But Ty was heavier and harder now than he had been as a schoolboy, and he stood up to all the punishment. "Boot camp wasn't too tough," he says now. "They ran us through the wringer, but anyone who was in condition got along all right. Where I had trouble was at Quantico. They started throwing formulae and data in our teeth. Well, I'd been out of school for eleven years and was rusty at all the business of lectures and note-taking and problem-solving and - oh, at studying in general. There I was, in there with fellows who'd just come from Carnegie Tech or M.I.T., trying to keep up with a course of study that galloped through years of college work in a few weeks."

Any actor, anyone with an artistic, creative imagination, is likely to find that advanced technical studies are almost impossibly tough for him. In high school Ty's favorite subjects had been English, dramatics, and history. "I liked history best of all because it was easy," he once said. "I used to dramatize every historical situation in my mind - imagine it as a play. That way, history came to life and it was easy to remember."

But tables of statistics and textbooks of aerodynamics don't yield so readily to dramatization. It seems almost a miracle than an actor with no college training could get through Quantico. But Ty's lighting-fast brain, his "instinct for the jugular", and his battering-ram determination carried him through. He got his second lieutenant's commission, went on to Corpus Christi for flight training, then on for more advanced training at Atlanta, Cherry Point, El Centro. Finally, In February 1945, he shipped out as a first lieutenant in the Marine Transport Command.

He found himself based at Kwajalein, flying the big C-46 transports over Jap-held areas. Later he moved up to Saipan, then to Okinawa and Kyushu, making long flights to such distant points as Guam, Nagoya and Tokyo. Presumably he ran into his share of Japflak and Jap fighters before the war ended, but he briskly dismisses the subject. There are officers in the Marine Corps, however, who have said privately that his war record will stand up with any man's.

Ty made firm friends in the Marines -- particularly with three buddies who flew with him in the Pacific: one an Oregon boy, another from Texas, another from Niagara Falls. He still writes to them.

He came home from the war in November of last year and whisked Annabella off to New York for a delirious round of parties with old friends. Then the couple dashed on to Canada for a month of skiing and playing in the snow before returning to Hollywood.

Ty was itching to get back to work. "I'm glad they gave me a good meaty role for my first job," he said. "Swashbuckling pictures like The Black Swan will be fun to get back into later on, but right now I want a part that demands serious thought -- and I have it in The Razor's Edge."

As always when he plays a serious role, Ty does plenty of heavy thinking about his new part. He's read a whole stack of books to steep himself in the background of the story; and several times he's slipped off for a weekend in the desert with Clifton Webb, producer Darryl Zanuck and director Edmund Goulding -- ostensibly for social relaxation, but actually to sit down with them and discuss the script for hours at a time. Ty prepares so thoroughly for a role that he likes to go over it line by line, suggesting slight changes here and there to make the phrasing more natural for his personality.

The Ty Power who has come back to Hollywood looks very like the one who left three years ago. Perhaps his face is slightly fuller, perhaps his chest and shoulders are slightly thicker, but the difference is so small it may not be visible on the screen. His manner seems the same too -- he still has that friendly way of looking straight into your eyes as he talks to you, and of shaking hands as if he really means it. He still talks rapidly and easily, and he is still full of pent-up energy that makes him as dynamic as a coiled spring.

I can't detect much change in myself, except that I'm not so impatient as I used to be," he says. "The war game me more tolerance, I believe -- a willingness to wait calmly while other people make up their minds, and to let situations work themselves out."

All of which leads an outside observer to suspect that Ty Power may be his own severest critic. It's been years since anyone accused him of being impatient or intolerant. The talk has always been, around Hollywood, of his friendliness and consideration for other people. His secretary and his stand in-, who would normally be exposed to as much of his "impatience" as anyone, have both stayed with him throughout his Hollywood career -- a striking testimonial to the affection Ty inspires in people who work with him. And today, among everyone who has had any contact with Tyrone Power, there is obvious delight that he's back in Hollywood. Over the years, his boyish remark that "we may not get all we want, but we'll get all that's good for us," has proved to be a mighty good working philosophy.

non-profit site

© 2004-2011 tyrone-power.com

all rights reserved